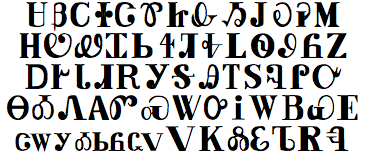

My friend Sean M. Burke was complaining on IRC about how this font he was reading was hurting his eyes. As a linguist and programmer specializing in Native American languages, he was used to his share of unusual scripts, but he couldn’t abide this one. He had a point.

Knowing that I was a bit of a typography geek, Sean asked if I could do anything to help. He was working on a book of Cherokee verbs, and was not looking forward to months of staring at the above font.

I ended up making this font. Click the buttons to see the difference.

Ironically, although I thought I was bringing new usability principles to the syllabary, I eventually found out that I was bringing the script closer to what it was intended to be all along. The original genius of the inventor of Cherokee script was finally coming through after all these years - both preserved, and obscured, by technology.

I am not a scholar of Cherokee, but here’s the story as I understand it, from what research I can do online and from the few books on the topic. [1] This is just the story of one amateur typographer, working in 2002 and 2003.

The traditional Cherokee font

Cherokee is unique in that it’s a script for a Native American language invented indigenously, by a person not literate in any language. Sequoyah had seen the “talking leaves” used by Westerners, and determined to bring the innovation to Cherokee. After a decade of experimentation he created a “syllabary” (one glyph per syllable) which worked well for the language. This intellectual achievement is unprecedented in history - jumping from illiteracy to Prometheus in a single lifetime. I don’t know what kind of a genius you have to be to accomplish this, sometimes against the prejudice of your neighbors, who are worried this is some kind of witchcraft. But Sequoyah was that kind of person.

The Cherokee rapidly adopted the syllabary, and it was soon brought to hot metal type. Cherokee newspapers were created, and Bibles printed.

Although Cherokee syllabary is used to this day, the Bible is still the longest text that most Cherokee have ever encountered which uses the script. So the syllabary acquired a religious dimension as well; one needed to learn this not just to be true to one’s culture, but to get closer to God.

The syllabary was copied, apparently from the original cuts in the 1800s, into various media until it finally landed in digital form in the font shown at the beginning of this article.

When I encountered it in 2002, the digital font offered by the Cherokee nation was clearly a copy of a copy of a copy. The serifs were mere blobs. Some glyphs were quite distorted.

Worse still, some (apparently) inherent flaws of the script seemed almost insurmountable.

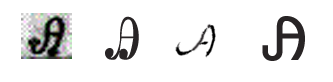

- Certain glyphs are nearly identical, such as

and

and  .

This was particularly nasty, and was apparently a common stumbling block for

those learning the language. Unfortunately this difficulty was rationalized, and even cherished, as part of the arduous

task of getting to understand the word of God.

.

This was particularly nasty, and was apparently a common stumbling block for

those learning the language. Unfortunately this difficulty was rationalized, and even cherished, as part of the arduous

task of getting to understand the word of God. - Many glyphs are distinguished only by having certain kinds of serifs or terminals. It would be as if an W in Bodoni and a W from Garamond were in the same character set, meaning different things.

And aesthetically, there were other unfortunate aspects:

- The typographic color was very uneven. Some glyphs were blacker than black, and others had hairline strokes.

- There seemed to be no logic behind the forms. We are used to scripts having a certain look, to combining a certain set of ideas, but Cherokee gathered its forms from absolutely everywhere. Some were identical to Latin typography, others seemed almost scribal, and still others were chimeras.

For traditional, book typography, we aim for a harmony of ideas, a minimum of ideas, evenness and balance in color. Getting there seemed like it was going to be difficult indeed.

My strategy

I’m a believer in the collective genius of people to eventually work around whatever problems technology imposes on us. So I reasoned that handwritten Cherokee might have sanded away all of the difficulties of the official font. I asked Sean and the other linguists working with him for samples of handwritten Cherokee, which they supplied. For certain rare glyphs, I would write them myself, over and over, until I felt the basic forms of the glyphs emerged.

I decided the basic template would be Microsoft’s Verdana, since it was a common font and worked online as well as offline. Making it compatible with a web-ready font would ensure that the basic forms were very, very clear. Also, this would give end users more options, since if it worked with Verdana, it would harmonize well with other free fonts available at the time from Microsoft. In 2002, high quality, online-ready fonts were a rarity.

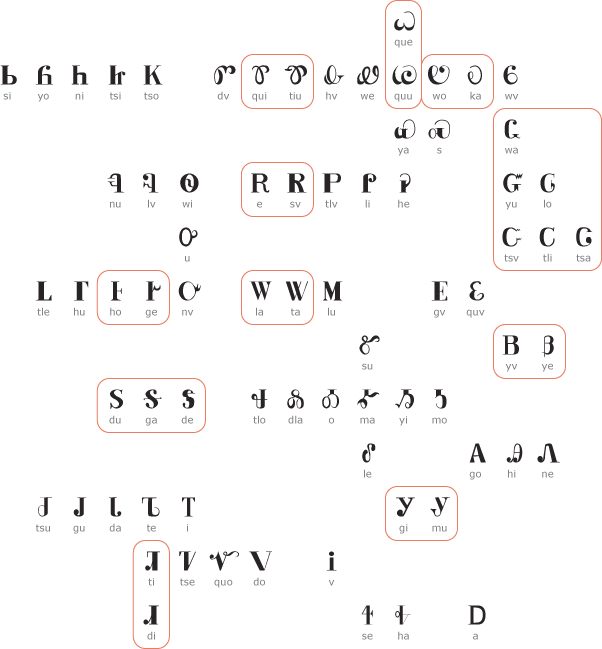

And there were a few other rules. My philosophy of type design is that it’s a system for distinguishing glyphs. Thus, how we achieve differences between glyphs is as important as how we make them similar. My rules for this font were as follows.

- Glyphs could not be distinguished by:

- variations in weight

- presence or absence of stroke terminal

- type of terminal (ball versus serif)

- anything too subtle to see in a font at reduced size

- All such decoration would be removed, until the form could be written with a monoline pen.

- If this resulted in glyphs that were too similar, subtle differences between glyphs would be exaggerated until they were obvious.

- Serifs, if they were required, would be exaggerated into a cross. Ball terminals would be eliminated entirely.

But it wasn’t all about change:

- Each glyph should be instantly recognizable to someone already familiar with the traditional Cherokee font.

- If, given the examples from handwritten Cherokee, certain aspects of these glyphs seem to be important to preserve, then they are preserved.

This chart shows some of the difficulties and how they were solved. Glyphs which use the same basic forms are grouped together visually, and particularly hard-to-distinguish glyphs are highlighted in red:

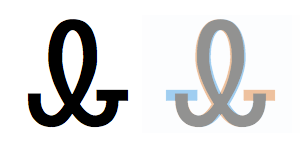

You can see some of these principles in the design for  and

and  . The minimum required to distinguish these characters would be

a vertical loop ending in a cross, like a “fish” form oriented vertically. But every handwriting sample faithfully preserves the prominent serif on one side. So I was careful to

recreate that, but also try to make the glyph seem balanced.

. The minimum required to distinguish these characters would be

a vertical loop ending in a cross, like a “fish” form oriented vertically. But every handwriting sample faithfully preserves the prominent serif on one side. So I was careful to

recreate that, but also try to make the glyph seem balanced.

I made one last change to the font, which wasn’t necessitated by any of my rules. The glyph Ᏸ (YE ) is the only one in the entire syllabary which always requires a descender. This seemed to be snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, as this would necessitate extra space between lines, only for this relatively rare syllable. Signage and many other applications would be easier if every word in Cherokee fit neatly into a rectangle. So I made my YE exaggerate the stroke to the left, to highlight where strokes intersected, but it had no descender.

Restoring, by innovating

It might seem a little bit arrogant for me, a Canadian with mixed Indian and Celtic heritage, to be meddling with one of the great cultural achivements of a Native American people. One of the flaws in this process was that I wasn’t working directly with end users, other than non-Cherokee linguists, and getting some indirect feedback from end users. Others since then have done much better by directly involving Cherokee community leaders.

But, there was one advantage of my isolation. I think an excess of reverential piety had kept the script from properly evolving for decades. I think someone like Sequoyah would have been shocked that we hadn’t improved on his work more.

And in this case, by meditating on these glyph forms for a few months, I might have found a way back to what Sequoyah originally intended.

When this font was almost finished, I had a revelation. Cherokee Syllabary wants to be scribal. It doesn’t want to be a roman. It wants to be more like an italic.

Look at the glyphs reminiscent of S, such as Ꮥ (DE ) and Ꭶ (GA ). With lines crossing through them, it’s hard to read, even a bit brutal. But it becomes graceful when

that S shape is elongated and at an angle, like an integration sign, that is, ∫ . Same thing with Ꮻ (WI ). The stair-step is hard to balance

within the O-shape, but translated to an italic, it would be a gentle wavy downward stroke.

It made me want to rip up what I did and start over, but the project was near completion so I shelved the idea.

And then I found out this was more or less what Sequoyah originally designed.

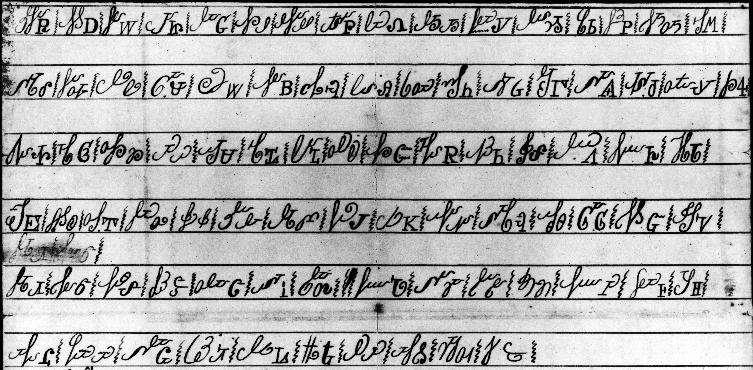

The above is a sample of Sequoyah’s original designs for Cherokee letters. This is a little bit hard to understand, because he’s relating an earlier cursive design for the script to a simplified version, more suitable for print.[3] So just look at the second glyph of each pair.

As you can see, the difficult distinction between  and

and  just isn’t there. Instead the

just isn’t there. Instead the

and

and  are easily distinguished by an upwards-curved short tail versus a straight tail that reaches the baseline.

are easily distinguished by an upwards-curved short tail versus a straight tail that reaches the baseline.

Which is exactly what I came to after sweating over that design for weeks,  versus

versus

. It’s eerie. It’s like the glyphs somehow encoded that information, latently.

. It’s eerie. It’s like the glyphs somehow encoded that information, latently.

So how did Cherokee end up with a font that was so far from the initial designs?

It seems that Samuel Worcester, the missionary who helped establish the first Cherokee newspaper, inserted himself into this process. He arranged to cast the letters in metal, and in so doing altered some of the basic designs and also moved it more in the direction of Latin typography.[4]

I wonder if Sequoyah was dismayed by some of the problems, or if he was pragmatic, and just happy to see his designs coming off a printing press and embraced by his people. I guess we’ll never know.

It’s a curious fate that heralds some of the problems with creativity in the 20th and 21st century. Nowadays, we encounter every work of creativity in a form suitable for mechanical reproduction. One downside is that the artifacts of this process, the accidents and mistakes, become a nearly immutable part of the work. The creak of a piano bench becomes part of a Beatles song, forever. In previous ages, a design, a story, or a song was reproduced from person to person, possibly for centuries, before it was fixed in a form that is no longer shaped by human hands.

So the Latin-speaking countries perfected the design of their alphabets over two millenia. Someone like Sequoyah had to get it right the first time. Or, if he wanted to change it, he would have to undertake the expense of labor and materials. And then his new vision would have to compete with the existing, mechanically reproducible works, already making copies of themselves in the environment.

Perhaps with digital technology, and movements like open source licenses, and Creative Commons, the balance of power is shifting, and we’ll always think of such works as fluid and alterable. Technology will then obscure who exactly who created things, make it difficult to compensate creators. But neither will it preserve mistakes fixed by one moment in time.

Reaction

Sean liked my font, which was enough for me.

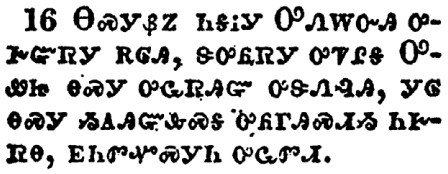

A Handbook of the Cherokee Verb [2] was released in 2003. In November 2014, it was made available for anyone to download. Here’s page 106:

An academic review mentioned it:

The typeface chosen for the syllabary is an easy-to-read sans serif font, much more inviting than the commonly used intricate characters derived from nineteenth-century models. Neil Kandalgaonkar, credited with designing the font, has done an admirable job.[5]

Future directions

nkCherokee was a drop-in replacement for the old official Cherokee nation typeface, which simply substituted glyphs onto the standard American typewriter keyboard. Since then, we’re in a more enlightened age, and proper Unicode encodings are more common.

My font was at best utilitarian, and since then, some professional, gorgeous fonts have been produced, like Plantagenet.

I still think that some of these projects are hewing too closely to the traditional Cherokee font. Here’s an example of one, Aboriginal Sans, in which some of the infelicities of 19th-century printing technology are still preserved. You can see how they make it difficult to distinguish characters at smaller sizes.

Microsoft made a similar sans serif font called Gadugi which is reasonably good for computer interfaces, and balances respect for the originals with modern demands for legibility.

But there’s still a great opportunity for some enterprising typographer who wants to try crafting a more scribal font for Cherokee.

Notes

1. Bender, Margaret. (2002) Signs of Cherokee Culture: Sequoyah’s Syllabary in Eastern Cherokee Life., University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8078-2707-9, ISBN 978-0-8078-5376-4. UNC Press link

2. A Handbook of the Cherokee Verb: A Preliminary Study (Feeling, Kopris, Lachler, and van Tuyl), Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Heritage Center, 2003. Pp 252. ISBN 0974281808. Search for it on WorldCat

3. The Cherokee Syllabary from Script to Print, Ellen Cushman, Michigan State University, *Ethnohistory* 57:4 (Fall 2010) DOI 10.1215/00141801-2010-039

4. Creating Cherokee Print: Samuel Austin Worcester’s Impact on the Syllabary, Wm. Joseph Thomas, Cornell University, 2008. ISSN 1940-8862

5. International Journal of American Linguistics - Volume 72, Issue 2, April 2006, pp. 285-287; A Handbook of the Cherokee Verb: A Preliminary Study (Feeling, Kopris, Lachler, and van Tuyl). JSTOR archive link

In other forms

I updated this for a talk that I gave at Vancouver Type Brigade #20. Here are the slides.

Other sites

The nkCherokee font is available for download (or modifications) at this Github repository.

Roy Boney’s Illustrated timeline of Cherokee Syllabary (Internet Archive link; original seems to be down)

Notes on the design of Microsoft’s Gadugi font, which followed a similar process but with far more feedback with Cherokee authorities.